|

PERSEPOLIS

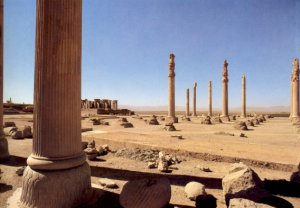

Persepolis was one of the ancient capitals of Persia, established by Darius I in the late 6th century BC. Its ruins lie 56km (35 miles) north-east of the city of Shiraz, the mountainous region of south-western Iran, where the dry climate has helped to preserve much of the architecture. Darius transferred the capital of the Achaemenian dynasty to Persepolis from Pasargadae, where Cyrus the Great, founder of the Persian Empire, had ruled. Construction of Persepolis began between 518 and 516 BC and continued under Darius's successors Xerxes I and Artaxerxes I in the 5th century BC. Known as Parsa by the ancient Persians, it is known today in Iran as Takht-e Jamshid ("Throne of Jamshid") after a legendary king. The Greeks called it Persepolis. At its height the Persian Empire stretched from Greece and Libya in the west to the Indus River in present-day Pakistan in the east. The many nations under the empire's rule enjoyed considerable autonomy in return for supplying the empire's wealth. Each year, at Noe-Rooz (the national festival of the vernal equinox) representatives from these nations brought tribute to the king. The Persian kings used Persepolis primarily as a residence and for ceremonies such as the New Year's celebration. The actual business of government was carried out mainly at Susa and Ecbatana. Persepolis consists of the remains of several monumental buildings on a vast artificial stone terrace about 450 by 300 m (1,480 by 1,000 ft). A double staircase, wide and shallow enough for horses to climb, led from the plains below to the top of the terrace. At the head of the staircase, visitors passed through the Gate of Xerxes, a gatehouse guarded by enormous carved stone bulls. Behind Persepolis are three sepulchres hewn out of the mountainside; the facades, of which one is incomplete, are richly ornamented with reliefs. About 8 miles (13 km) north by north-east, on the opposite side of the Pulvar River, rises a perpendicular wall of rock in which four similar tombs are cut at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley. This place is called Naqsh-e Rostam (the Picture of Rostam), from the Sassanian carvings below the tombs, which were thought to represent the mythical hero Rostam. That the occupants of these seven tombs were Achaemenian kings might be inferred from the sculptures, and one of those at Naqsh-e Rostam is expressly declared in its inscriptions to be the tomb of Darius I, son of Hystaspes, whose grave, according to the Greek historian Ctesias, was in a cliff face that could be reached only by means of an apparatus of ropes. The three other tombs at Naqsh-e Rostam, besides that of Darius I, are probably those of Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II. The two completed graves behind Persepolis probably belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. The unfinished one might be that of Arses, who reigned at the longest two years, but is more likely that of Darius III, last of the Achaemenian line, who was overthrown by Alexander. The largest building at Persepolis, the Apadana (audience hall), stood to the right of the gatehouse. Archaeologists estimate that it could accommodate 10,000 people. Massive stone columns supported the Apadana's roof; 36 were interior columns and another 36 supported verandas on three sides of the building. Thirteen of these 72 columns remain standing today. Remnants of the Apadana, Persepolis Stone doorways and 13 of the 72 massive stone columns that originally supported the Apadana, or audience hall, at Persepolis are still standing today. Each column was 20m (66ft) tall and was topped by an elaborate capital. The double-headed animals at the top of the capitals once supported wooden roof beams. Monumental staircases decorated with elaborate sculpture in relief led to the Apadana, which stood on an elevated platform. The relief sculpture depicts the ceremonial procession that took place when representatives from the conquered nations brought gifts to the king. The procession is led by Persians and Medes, the peoples whom Cyrus the Great united to found the Persian Empire. After them come delegates bearing gifts: The Elamites bring lions, the Babylonians a Brahma bull, the Lydians bolts of cloth, and so forth. Because the east staircase lay buried beneath ashes and rubble for centuries, its delicately carved relief sculptures remain in excellent condition today. Next to the Apadana was the Throne Hall, the second largest building at Persepolis, where the king received nobles, dignitaries, and envoys bearing tribute. An enormous throne room, 70 by 70m (230 by 230ft), occupied the central portion of the Throne Hall. It is also known as the 'Hall of a Hundred Columns' after the 100 columns that supported its roof. These columns were made of wood, and only their stone bases survive today. Eight stone doorways led into the throne room. Carvings on the sides of the doorway depict the king on his throne and the king in combat with demons. The Throne Room was begun by Xerxes and completed by Artaxerxes I. The Treasury stood next to the Throne Hall. This enormous building served as an armoury and a storehouse for the tribute brought to the king on New Year's from the subject nations. It also held booty taken from the nations conquered by the Persian Empire. Beyond the Apadana lay the Palaces of Darius and Xerxes. The Palace of Darius, the Tachara was reached by stone stairways decorated with carvings of servants carrying animals and food for serving at the king's table. Carved reliefs also decorated the stone jambs of doorways. The subjects depicted on these jambs include the king fighting lions, servants bringing towels and ointments to the king, and attendants shielding the king with umbrellas and flywhisks. A number of the stone doorways are still standing. The Palace of Xerxes, The Hadish, was nearly twice the size of the Palace of Darius and had similar carved reliefs on stairways and doorframes. Living quarters for the king and separate quarters for the women and the servants stood next to the palaces. Persepolis was destroyed slightly less than two centuries after it was begun. Alexander of Macedonia plundered Persepolis and then set fire to it in 330 BC. According to Greek biographer Plutarch, he needed 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels to carry away the treasure looted from Persepolis. In 316 BC Persepolis was still the capital of Persis as a province of the Macedonian empire. The city gradually declined in the Seleucid period and after, its ruins attesting its ancient glory. In the 3rd century AD the nearby city of Istakhr became the centre of the Sassanian empire. The site is marked by a large terrace with its east side leaning on the Kuh-e Rahmat (Mount of Mercy). Persepolis was eventually abandoned, and it lay buried beneath ashes and rubble until its rediscovery in 1620. Although many people visited Persepolis in the next centuries, excavation of the ruins did not begin until 1931, under the direction of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 halted this work. The Iranian Archaeological Service continued the excavation and restoration of Persepolis after the war.

Copyright shall at all times remain vested in the Author. No part of the work shall be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the Author's express written consent. Copyright © 2002 K. Kianush, Art Arena |

|||||||||||